Before reaching out to Sebastian Sons, I read extensively about his work. What stood out most to me was his sensitivity to understanding the nuances of what he knows and doesn’t know about Saudi Arabia, his ability to accurately translate the differences in mentality, and his skill in placing issues appropriately. After speaking with him, I understood that his main driving force is his belief that only by connecting people can we truly understand each other.

Q: From what you’ve said, it seems like you mainly talk to younger people. Am I correct?

A: I wouldn’t say I only talk to the young, but I am particularly interested in understanding the issues and thoughts of this generation, which I call the ‘Generation MBS,’ especially in relation to their parents, who didn’t have these opportunities. It’s easier to connect with younger people because the government promotes this.

Older people, however, are no longer as prominently supported, which I find unfortunate. The political and economic relevance of people in their 40s and 50s remains significant. There are also many individuals from this generation, like high-ranking political representatives, who are very capable and crucial for this transformation.

Q: Saudi Arabia is a conservative society. How does this manifest today? Are we still relying on our identity as Saudis, or do we finally have something to say?

A: I have definitely noticed a growing sense of self-confidence, particularly in how Saudi Arabia wants to be perceived as an independent actor. This is especially evident in Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states, where nationalism is less tied to religion compared to the past.

Vision 2030, for me, is primarily a label that provides orientation on what it means to be Saudi, not defined solely by religion but by broader aspects of Saudi identity. This has led many young people from the West to perceive Saudi Arabia in a more favorable light. The Vision is a top-down approach but also considers what parts of society want.

Over the past years, trust within the population has grown, while trust from the West has declined. Saudi Arabia no longer wants to be seen merely as a place that pleases the West. Instead, it aims to act as an independent player, engaging with the US, China, and others while pursuing its own agenda. This national pride is a form of intellectual nationalism.

Q: Has this message reached Germany/Europe?

A: I believe it depends on who you ask. For instance, the economic developments are well-received. Many Germans in business understand that they need to offer something distinctive compared to Chinese, American, or French competitors. They must work hard and not rely solely on the "Made in Germany" reputation.

Instead of focusing heavily on PR branding, the exchange between Saudi Arabia and Western countries such as Germany should emphasize people-to-people contact. I believe that authenticity will help the most. Cultural exchanges, student programs, art exhibitions, and journalism are crucial.

Q: The reporting on Saudi Arabia is still very negative. Why is that?

A: There are several reasons for this. One is that it’s challenging to talk about Saudi Arabia without falling into clichés. What can be done to make the transformations in Saudi Arabia more recognized? Both sides, including Saudis, need to have the courage to pursue smaller projects that promote genuine understanding and exchange. These don’t have to be grand projects but should focus on authenticity and presenting a true picture of Saudi Arabia.

At the end of the day, Saudi Arabia is often still associated with negative stereotypes, like wealthy sheikhs from the desert investing billions of dollars to bring international music or sports stars to the Kingdom instead of focusing on ‘normal people’ exchanges.

Q: Is it true that Germans believe Saudis are involved in sports washing?

A: It’s a mixed picture. I have spoken with many people in the sports industry who do not view Saudi Arabia’s involvement as sports washing and are open to collaboration. In Germany, there is some hesitation, whereas in other countries like the UK and Spain, there is less fear of engagement.

Sports offer an opportunity, whether it's watching football or playing video games. However, this doesn’t mean that criticism is excluded. There is self-reflection involved, and sports provide a chance to engage in constructive and respectful dialogue.

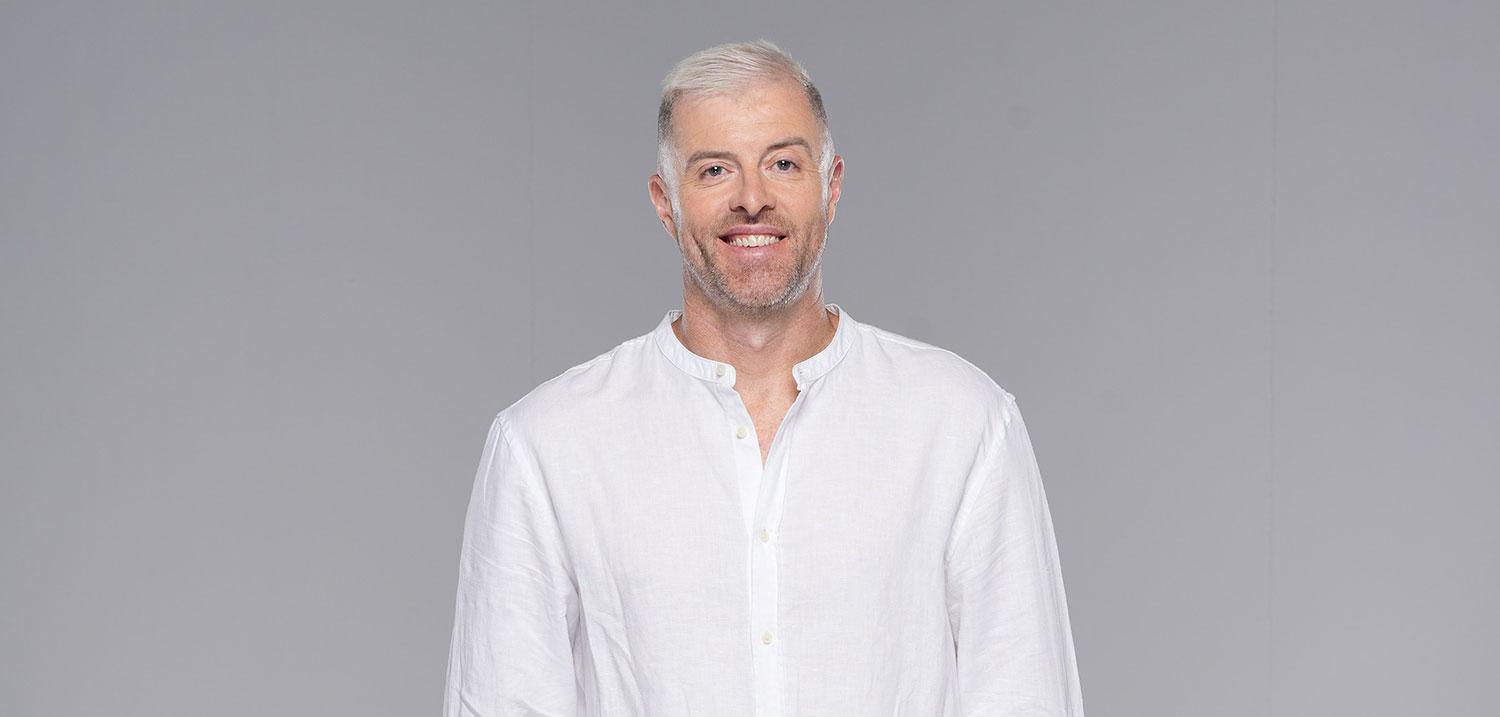

About Sebastian Sons

Sebastian Sons is a German scholar and expert on the Gulf region, known for his incisive analyses of Saudi Arabia’s societal and political transformations. With a focus on fostering dialogue, he has examined the Kingdom’s Vision 2030 reforms, its evolving identity, and its relationship with Europe. Sons emphasizes the importance of people-to-people exchanges over PR branding, advocating for a more authentic narrative about Saudi Arabia. His work reflects a balanced approach, highlighting both opportunities and challenges in bridging the cultural and political divides between Saudi Arabia and the West.

0 Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!