In a society increasingly shaped by screens and the speed of digital life, the quiet return of board games in Saudi Arabia might seem improbable. And yet, across homes and cafés in cities like Jeddah and Riyadh, Saudis are rediscovering the appeal of sitting down, in person, for a round of something that doesn’t require charging.

Games like Jackaroo, Saudi Deal, and Elaab Bel Khames are becoming fixtures at weekend gatherings and family nights. A recent Arab News feature pointed to the growing popularity of locally designed games that reflect Saudi humour, habits, and group dynamics. As one player put it, “Playing face to face just hits different.”

This return to analogue interaction is often described as a trend, but for many Saudis, it feels more like a return to something far older.

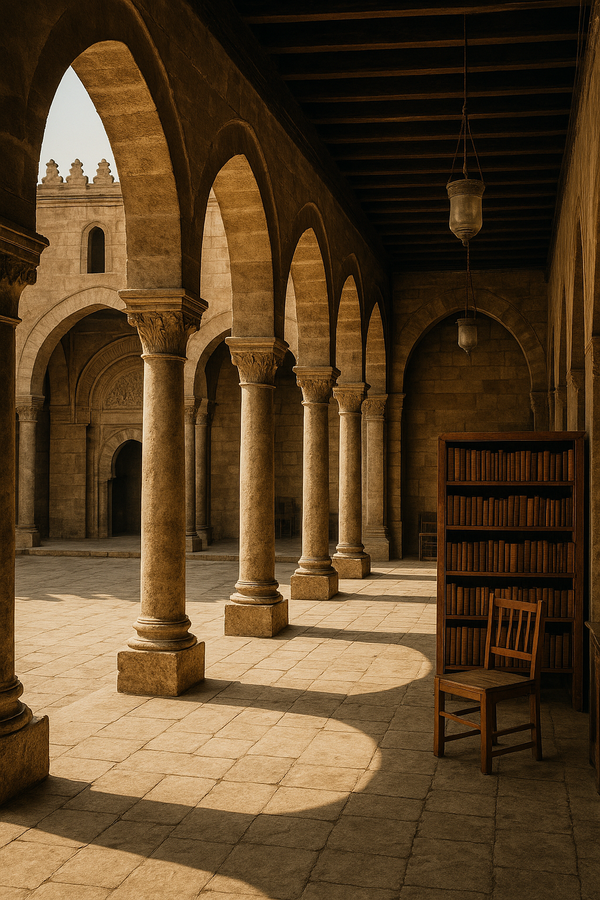

In the 1980s, games were an ordinary part of domestic life. One could observe uncles, cousins, and even the occasional manager and employee sitting around a Baloot table with quiet intensity. Baloot, a four-player card game derived from the French Belote, was traditionally a male pursuit. It relied on strategy, subtle signals, and restraint. Hierarchy at the table was never formal, but if a junior player happened to outplay his superior, the next day in the office might carry a trace of the previous night’s outcome.

Carrom—known locally as Keram—played a different social role. The game, which involves flicking small discs into corner pockets on a wooden board, was more inclusive. It brought together children, guests, and women. Despite its simple appearance, it required precision and a certain stillness in the hand—an unspoken discipline. It was not a loud game, but a focused one. And in that quietness, people connected.

These games gave structure to time. They allowed people to gather without the demands of formal hosting. One didn’t need to be particularly talkative, accomplished, or even familiar with others to join—just present. For a while, titles and age differences were suspended.

What is notable about today's resurgence is how it draws from that same principle but adapts it to a changing society. Locally developed games now feature colloquial language, pop-culture references, and shared jokes. They speak, quite literally, in a language players recognise as their own. This cultural familiarity is part of their appeal. As one interviewee noted, “They speak our language—literally.”

That board games are now played in cafés, among mixed-gender groups and younger players, signals a shift. They are no longer background diversions but active forms of social connection. In a fast-moving country where routines and roles are being renegotiated, board games offer something slower, tactile, and familiar.

This revival is not about nostalgia, nor is it a rejection of modernity. It is a quiet reminder that social connection does not always require reinvention—only space. The formats may have evolved, but the core remains unchanged: a way of being together, without needing to say much at all.

0 Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!